Welcome

Alex Stitt

Director of Lloyd’s Register Foundation, Heritage Centre

Welcome to the next edition of Dispatch. Happy New Year! 2024 was another brilliant year for the Heritage Centre. From the launch of new grants with the University of Portsmouth, the National Maritime Museum and the University of the Arctic to convening two global workshops on Potentially Polluting Wrecks and opening SHE_SEES in Portsmouth Historic Quarter.

Lloyd’s Register Foundation also launched its new strategy for 2024-2029. At a glance, the three priority areas for the Foundation are: Safer Maritime Systems, Safer Infrastructure and Skilled People for Safer Engineering.

We have lots to look forward to in 2025!

Alex

Small Grants Scheme Round Up

The Common Room: Northern Coal Shipments, Navigating Global Impact in a Warming World

The Common Room, Newcastle, UK, is an archive, charity and heritage venue holding one of the largest public collections of archival material relating to the development of the coal-trade and its allied industries, including shipping. For coal mining to be profitable, the product had to be transported. Shipping coal was key to fuelling industrial expansion from the Northern Coalfields across the UK in the 18th century.

The grant will cover volunteer research within our Lloyd's Register Heritage Centre collection to inform a digital exhibition about the exportation of coal and new shipping technologies from the Northeast across the globe. Interpretation will centre around sustainability and assessing the long-term climate impacts.

National Life Stories: Exploring Innovations in Maritime Safety

National Life Stories [NLS] seeks to explore innovations in maritime safety through in-depth personal testimony. Using two long life story recordings, the grant will examine developments in the design and engineering of vessels and ports and the formulation of health and safety policy. The interviews will record specific changes, new technologies and approaches to risk management, documenting how institutional and policy change is instigated, introduced and evaluated. Interviews will be archived at the British Library in perpetuity and made available for research.

West Sussex County Council: Cataloguing the Marine and General Mutual Life Assurance Society Archive

This project will see a qualified archivist catalogue and repackage the Marine and General Mutual Life Assurance Society (MGM) Archive over eight weeks to make it accessible to researchers at West Sussex Record Office (WSRO). Founded in 1851, MGM provided life assurance to mariners. The collection consists of the company’s business records between 1852-2000s and includes material such as minutes, financial records, and policy registers.

Lancashire Archive & Local History, Lancashire County Council: Fleetwood’s Coastal Past

The grant will promote Fleetwood’s maritime heritage from the Lancashire Archives & Local History (LA&LH) collections through digitisation, public display at Fleetwood Library and digital records made available online via Red Rose Collections, and through the listening post at Lancashire Archives & Local History for researchers to consult.

Gloucestershire Archives: Gloucestershire Mariners

This project will see a qualified archivist to catalogue and repackage the Marine and General Mutual Life Assurance Society (MGM) Archive over eight weeks to make it accessible to researchers at West Sussex Record Office (WSRO). Founded in 1851, MGM provided life assurance to mariners. The collection consists of the company’s business records between 1852-2000s and includes material such as minutes, financial records, and policy registers.

National Historic Ships UK: Don’t Rock the Boat, Stability Guidance for Static Floating Heritage

This grant will research, develop and publish accessible guidance material for the owners of static floating historic vessels, contractors and service providers to the industry. Previous work and stakeholder engagement has identified a lack of guidelines and stability criteria for static vessels and similar floating structures which are open to the public. This issue is a key concern for historic vessels when they cease seagoing activity but remain afloat, with the need to create a safe environment for their users and retain significance.

The University of Portsmouth: Re-IMAGEnging Port Cities, Diversifying Portsmouth Maritime History by Co-designing Interactions

Port cities’ heritage portrays a problematic vision of colonial past that implicitly alienates communities who are underrepresented within maritime collections. This grant will co-design an interactive storytelling intervention using Portsmouth City Council Museum’s collection to facilitate the discovery of hidden histories and reflect on communal diversity, past, present and future.

The project will evaluate audience engagement and the educational opportunities of creative technologies to facilitate discourses around diversifying maritime heritage. This approach advocates for a proactive democratisation and reinterpretation of collections, challenging misrepresentation, thus creating social impact and engaging diverse audiences at the heart of communities.

Maritime Archaeology Sea Trust: Royal Navy Loss List, Interlinking with NMRN and MoD Salmo

The grant will link the following three databases:

➜The Royal Navy Loss List (RNLL) is a fully searchable research tool that covers all Royal Navy vessels recorded as sunk or destroyed from 1343 to 2011.

➜The National Museum of the Royal Navy (NMRN) Finds Catalogue. This comprises its entire collection, detailing the artefacts and documents in its possession.

➜MoD Salmo database of Legacy Merchant Ships employed by MoD at the time of sinking (many are PPWs).

Highland Archive Service, High Life Highland: Following the Fish, Stories of the Herring Girls

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries hundreds of women left the Western Isles to travel north to Caithness then down the Scottish coast into England following the herring fleets. ‘Following the Fish’ seeks to research and tell the story of these women, their backbreaking work, and their vital importance to our national maritime history. Both individual stories and general context will be researched through collections held by the Highland Archive Service, Suffolk Archives, Norfolk Archives and Tasglann nan Eilean, resulting in the creation of an online exhibition, two sets of touring banners and two launch events (in Scotland and England).

Like melting the polar ice caps, this process would likely take many decades or even centuries to complete, depending on the method used and the amount of water available.

SS Great Britain: Assembling the Great Western

Between 2024-29 the SS Great Britain Trust (SSGBT) is engaged in an ambitious project to recreate the earlier sister vessel of the Great Britain, the Great Western, in one half of Bristol’s last working drydock. The Great Western was the first purpose-built ocean-going steam vessel, and its successful launch and career marked a turning point in maritime history.

A significant initial phase for the SSGBT in this engineering project is to initiate significant collections activity that will allow the museum to curate, explore, and publicly engage with the fascinating stories of the people of the Great Western.

Maritime Archaeological Society of Finland: Identifying Potential Shipwrecks on the Gulf of Finland

Maritime Archaeological Society of Finland (MAS) is executing a long-term shipwreck surveying program “Baltic 3D Wreck Ontology”, which aims at surveying all historic shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea and producing a virtual 3D-model and a scientific dating of the shipwrecks. This program has been active since 2018 and has already produced more than 150 surveyed sites and 3D-models/datings thereto.

This grant will enable an additional 10-15 wreck sites to be surveyed, 3D-modeled, radiocarbon dated and reported to the Finnish Heritage Agency.

Swansea University: A Voyage of Discovery on the Avon Searider

For the UK to nurture new manufacturing industries that triumph in a globalised economy, lessons must be learned from companies that have achieved that, companies like Avon Inflatables, who engineered a safer world. Avon become synonymous with the best that inflatable boating could offer and launched the world’s first commercial RIB, the Searider, in 1969. Designed as a rescue vessel, their pedigree and heritage is legendary, but how they came to dominate their market remains unexamined. Employing a case-study approach, the grant will enable qualitative interviews and documentary film to investigate the people, processes, technology, and timings to understand the Searider’s success.

The Heritage Centre has recently been featured on History Hit, the world’s leading history podcast hosted by Dan Snow. Lloyd's Register Foundation collaborated on a mini-series ‘Ships that Made the British Empire’ that tells four stories of ships that have shaped Britain and its maritime history, from the trade that kickstarted the global food chain to the technology that revolutionised our ability to conquer the seas.

The Cutty Sark

The Cutty Sark was the fastest ship of her day and could carry over a million pounds of tea from China back to Britain for a thirsty Victorian public. She ruled the waves at the height of Britain’s imperial century as she carried trade goods across the globe as far as Australia. To make the treacherous journey across the world’s biggest oceans, she was equipped with state-of-the-art technology and surveyed by the Lloyd’s Register, the world’s first ship classification society.

Our Senior Archivist, Max Wilson and Archivist, Zach Schieferstein, met with Dan Snow, on board the Cutty Sark in Greenwich to delve into the story of this ship and what it tells us about shipbuilding and trade in the 19th century, plus the role Lloyd’s Register played in surveying and classifying vessels at that time.

The Greatest Tea Race of the Victorian Age

With towering masts and billowing sails, the Cutty Sark and the Thermopylae raced neck and neck through relentless waves to be the first to arrive in London with their tea shipment from Shanghai. The first ship back could claim the highest price for its cargo.

Max joined Dan Snow for a dramatic blow-by-blow account of this high-stakes race that gripped Victorians in the late summer of 1872, where fortunes were made and lost by the hour.

The Scottish Island, The Shipwreck and the Whiskey

In 1941, the SS Politician ran aground off Eriskay in the Scottish Hebrides Islands, carrying 260,000 bottles of whisky. As war rationing gripped Britain, Hebridean islanders saw the wreck as a godsend. Under cover of darkness, they salvaged thousands of bottles, hiding them in caves, haystacks, and peat bogs. A cat-and-mouse game ensued with customs officers who were determined to stop the whisky smuggling.

The Lloyd’s Register Foundation Senior Curator in Contemporary Maritime at the National Maritime Museum, Laura Boon-Williams, jointed Dan Snow to recount the true story behind the beloved movie Whisky Galore and tells us about the spirit of this Hebridean community during wartime, merchant shipping in WII and why a seemingly endless supply of whiskey wasn’t entirely a blessing.

With one foot in the present and one in the past The Mariner’s Mirror brings you the most exciting and interesting current maritime projects worldwide: including excavations of shipwrecks, the restoration of historic ships, sailing classic yachts and tall ships, unprecedented behind the scenes access to exhibitions, museums and archives worldwide, primary sources and accounts that bring the maritime past alive as never before.

Presented by Dr Sam Willis, supported by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation.

The Amazing History of Icebreakers

The ability to navigate in icy seas is one of the most important themes in the historical and contemporary story of human interaction with the sea. Over centuries of development ships are now able to operate safely in and amongst giant ice-islands or semi-submerged floes as deadly as any reef. Specialist vessels have been designed with strengthened hulls, unique bow designs and innovative propellers and rudders.

To find our more Dr Sam Willis spoke with Zach Schieferstein from Lloyd’s Register Foundation to discuss the historical development of icebreaker design and propulsion, the significance of the Arctic and Antarctic in geopolitics and the crucial role of Lloyd’s Register in the evolution of icebreaker design and construction.

Portsmouth Historic Quarter and the SHE_SEES Exhibition

The SHE_SEES exhibition, hosted in partnership with the Lloyds Register Foundation, Portsmouth Historic Quarter and the University of Portsmouth, taps into archive materials from across the UK and Ireland to uncover the extensive history of trailblazing female voices in the maritime industry and aims to change the tide on diversity. Dr Sam Willis speaks with Hannah Prowse CEO of Portsmouth Historic Quarter as well as historians George Ackers and Mel Bassett who worked on the background research bringing the historical voices to life.

Potentially Polluting Wrecks

In order to give an update on the exciting momentum of the Potentially Polluting Wrecks work that Lloyd’s Register Foundation is funding Project Tangaroa, led by The Ocean Foundation and Waves Group, Ben Ferrari (Project Manager for The Ocean Foundation) gives his account of the most recent Workshop that took place in Helsinki…

Project Tangaroa is convening expert stakeholders to develop global standards to develop global standards for the assessment and management of legacy wrecks, mostly from the two world wars, that still contain up to 20 million tonnes of oil and represent growing risk to safety, livelihoods and environment. Central to this programme is a series of three expert workshops.

The second Tangaroa Workshop was held in Helsinki this September. More than 70 experts from 15 countries shared experience and insight, consolidating the global network that now underpins Tangaroa’s mission. Further momentum was built towards the essential shift in emphasis from emergency response to strategic management of potentially polluting wrecks (PPWs). It also resulted in some important conversations about the future shape of the Tangaroa programme.

The venue was the 18th century fortress on the Island of Suomenlinna – a UNESCO world heritage site, impressive, austere and a hugely symbolic location given the current geopolitical situation in the Baltic region. Indeed, the surroundings were a constant reminder of the complex blend of safety, heritage, environmental and political factors that need to be addressed in management of PPWs.

Workshop one delivered a high-level synthesis of the current state of play with regard to PPWs. Workshop two focused on the practical: what techniques are currently available for assessment, evaluation and intervention; how do these measure up against the enormous challenge presented by the legacy of two world wars?

Day one looked at assessment methodologies and there are clearly some firm foundations on which technical standards can be built. While an enormous amount of work remains to be done, some government agencies are making commitments and making progress. In the break out sessions and over coffee, eavesdropping on conversations it was evident that even the most experienced practitioners were discovering new insights and contacts. The case-studies presented showed how new technology is proving invaluable in enabling progress with matters such non-intrusive assessment of residual oil quantities. Yet, it was also evident that, as hull structures deteriorate and climate impacts create new dynamics – especially where once frigid waters begin to warm - application of even tried and trusted techniques becomes more challenging and planned intervention becomes time critical.

Day two illustrated something special about Tangaroa – the ability of the team to convene industry experts to share information and experience in a way that is certainly rare in my experience. Presentations from the leading practitioners in the salvage and marine services industries showed that innovative engineering, allied to a large amount of determination, can achieve impressive results. We also learned that, in many instances, very difficult tasks are having to be completed with slim resources and that budgets for this critical work are under immense pressure.

So, given the global scale of the challenge and the vast ocean spaces involved – can we really aspire to a more strategic approach? It’s a fair question. Happily, presentations on use of satellite data and earth observation systems hinted that the answer can be a firm, ‘yes’. The presentations offered evidence drawn from previous as well as new coverage and ranged from site specific detail to large area surveillance. Our capacity to use this technology for detection and monitoring of spills is developing at speed. That is a huge advantage – especially as it creates opportunities for collaboration with other agencies and partners with a shared interest in satellite enabled ocean stewardship.

On day three, environmental assessment was addressed. Again, there was ample evidence of existing gold-standard practice that can be built upon – and also further confirmation that resources are lacking to apply this knowledge as broadly and programmatically as is urgently required. Presentations on operational challenges associated with oil spill response crystallised a sobering reality: in many locations where PPWs pose a threat, remoteness, lack of equipment stockpiles and lack of a local, trained workforce create a high risk of profound damage to environment and livelihood.

I don’t think anyone could have left the Workshop without a clear sense of the scale of the PPW challenge. Equally, everyone, I am certain, left with a strong sense that, through Tangaroa, we have an opportunity to marshal the expertise, the industry capacity and the powerful advocacy that is needed to rise to this challenge. In order to do that we also have to adapt our plans on the basis of new evidence and Workshop two has prompted some important decisions. Tangaroa will never lose focus on the urgency of coordinated action in the Pacific. However, it is obvious that we must also develop a high intensity programme in northern waters and the Arctic along with the Mediterranean. We know that dilapidation over time is a key cause of oil leaks but we have also been alerted to the impacts of climate change and, most perniciously, illegal salvage; both of these issues need to be addressed more directly than perhaps has been the case to date. The role of satellite data has also come to the fore – not a surprise but certainly an indication of the convening value of Tangaroa – connecting people and discovering new opportunities to leverage expertise from other sectors.

Workshop three will be held in Malta in March 2025. This event will focus on data access and archives. Beyond that we look forward to working with the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in order to build a pathway from expert consensus to taking global technical standards into use to make the change we need happen.

We are enormously grateful to: Juha Flinkmann from the Finnish Environment Institute; and Minna Koivikko from the Finnish Heritage Agency.

Introduction

Ballast was – and is – critical to the safety of all ships, with various materials used, including shingle, sand, stone and iron bars. Ballast needed securing to prevent it shifting and causing a catastrophe. Many vessels sailed ‘in ballast’ when they had no cargo. The provision of ballast was a substantial industry worldwide, and in past times much of the loading and unloading was done by hand.

Roy and Lesley Adkins are historians and archaeologists who live in Devon. They have written widely acclaimed books on social, naval and military history, including Jack Tar, Gibraltar, Trafalgar, The War for All the Oceans, Eavesdropping on Jane Austen’s England and When There Were Birds. They are Fellows of the Society of Antiquaries, Fellows of the Royal Historical Society and Members of the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists.

Ballast:

A Hidden History on How to Avoid Shipwreck

Colliers unloading coal into lighters in the River Thames (Pool of London) before being ballasted for their return journey, from Picturesque Europe: volume I The British Isles (1879) © R & L Adkins

A gang of four ballast-heavers is shovelling ballast from a lighter in the River Thames into the collier, from Henry Mayhew 1861 London Labour and the London Poor Volume III (1861) © R & L Adkins

What is Ballast? And What did it Do?

Although individual ships may have been expertly designed, skilfully constructed and many even given the highest rating by Lloyd’s Register, something as basic as ballast, a temporary and constantly changing load, was vital to a vessel’s survival. The word ‘ballast’ first appears in the English language in the late 15th century to denote any heavy material placed in the bottom of a vessel. This was crucial for the safety of ships, because ballast lowered the centre of gravity (the point where everything is balanced), improving stability and preventing the vessel from toppling over.

William Falconer was a Scottish poet, mariner and author of An Universal Dictionary of the Marine. First published in 1769, in it he defined ballast as ‘a certain portion of stone, iron, gravel, or such like materials, deposited in a ship’s hold, when she has either no cargo, or too little to bring her sufficiently low in the water. It is used to counter-balance the effort of the wind upon the masts, and give the ship a proper stability, that she may be able to carry sail without danger of over-turning.’ Merchant ships that carried a cargo like coal or grain rarely carried ballast, but a great deal could be necessary with a light cargo, such as tea, tobacco or wool, and the amount needed was a matter of trial and error. At the destination port the cargo was discharged, and any ballast required was loaded in readiness for the next cargo. If no cargo was available at that port, enough ballast had to be loaded before heading home or to another port for a cargo.

Some vessels started off without any cargo, a loss-making voyage, perhaps to Australia for grain, Chile for nitrates or Peru for guano, in which case they needed ballast for the initial outbound journey. The range of materials included gravel, shingle, sand, mud, stone, chalk, demolition rubble, industrial waste such as slag, bricks, tiles and iron pigs. Vessels described as ‘in ballast’ had ballast to ensure stability, but no commercial cargo, although the ballast might be a low-value cargo such as salt, chalk, coal, bricks or iron, which could be offered for sale on arrival. With shipwrecks it is not always possible to distinguish between ballast and the cargo. In April 1656 the Dutch East India Company ship Vergulde Draeck struck a reef on the coast of Western Australia, and underwater excavations have discovered about 8,000 bricks, often referred to as ‘ballast bricks’. They were actually intended for sale, as Company records show that thousands of bricks were transported by several of their vessels, including 26,000 on the Vergulde Draeck’s first voyage in 1653.

Sailing in ballast was not ideal from an economic or a safety point of view, but it was often done. Ships arriving or departing in ballast were routinely recorded in newspapers, like those mentioned by the Hull Daily Mail as arriving on 15 October 1925 at the Yorkshire port of Goole on the River Ouse:

On the next day eight more ships arrived, all in ballast, and although these Goole vessels had made only short journeys, many other ships routinely sailed in ballast on trans-Atlantic and trans-Pacific voyages.

South Shields (left) and North Shields (right) looking up the River Tyne towards Newcastle, with numerous colliers. © R & L Adkins

How Ballast was Obtained and How it was Loaded

All over the seafaring world ballast was essential, and the ideal ballast was inexpensive, heavy and easy to stow and secure. In order to avoid blocking pumps and spoiling cargoes, the preferred ballast was dry and solid, like stone. From the mid-19th century water ballast systems were increasingly used as well, so the term ‘solid ballast’ came to describe all non-liquid forms of ballast. The ballast had to be purchased, and because most destination ports charged for unloading it, some captains took risks in order to reduce costs.

Warships needed to be well ballasted since they carried a great deal of weight on gundecks, with their cannons and shot. Scrap ordnance, shot and shells were traditionally reused as ballast, but from the early 18th century pig iron became more common, cast specifically for the Royal Navy into bars known as pigs that usually measured 3 feet x 6 inches x 6 inches, though smaller versions were also produced. Referred to as kentledge ballast, many tons of these iron bars were loaded and stacked, before being covered with shingle and gravel ballast. Any iron pigs carried on merchant ships were generally curved and intended as trade items.

For almost three centuries from 1594 Trinity House had the rights of ballastage on the River Thames below London Bridge, with a monopoly on obtaining and selling ballast, and the profits went into establishing and maintaining buoys, beacons and lights. Colliers constantly brought coal to London from Newcastle and Sunderland, but without return cargoes they sailed back empty, apart from ballast for stability. The ballast was primarily sand and gravel dredged from the Thames, which kept the waterway clear, and it was deposited in Trinity House lighters and taken to colliers and other merchant ships for ballast-heavers to shift. Vessels could load other types of ballast, such as bricks and even London’s refuse and dung.

Cataloguing the Yacht Ship Plan and Survey Report collection

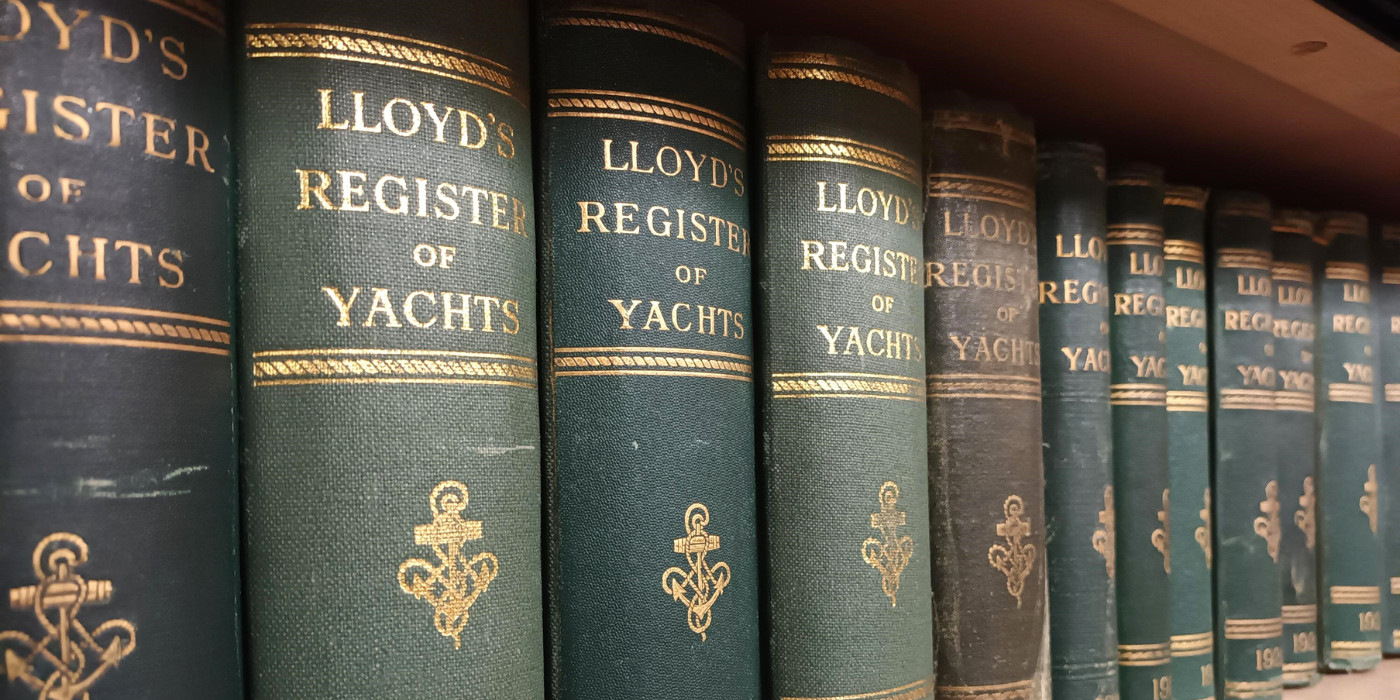

For the first time Lloyd's Register’s (LR) archive collection of Yacht survey reports and plans has been catalogued. The ‘Y series’ as this is known spans 1850s (the oldest is a survey report for the Yacht Dream dated May 1854) to the 1990’s and covers survey reports, plans, correspondence and related documents concerning the survey and classification of Yachts classed by LR. This is very much similar to the Ship Plan Survey Report Collection (SPSRC) which relates to seagoing ships over 100 gross tons rather than yachts and smaller crafts.

The Yacht Registration Society was established in 1877 and the Lloyd's Register of Yachts was first published in following year, prior to this point smaller craft were included in the Register of Ships. Rules and Regulations were also issued in this year. The Register of Yachts included particulars of classed and unclassed yachts until 1980. A Yacht department was established in 1852 and this developed into the Small Craft Department in 1987.

There is a total of 192 boxes of records, which equates to 48 linear metres. However, this will be increased once they have been rehoused, as they currently in non-archival envelopes. A mini project will be to rehouse all the records into conservation grade primary enclosures. Though this is no small tasks as there are some 3,534 files/envelopes including over 49,000 records.

We catalogued these to file level, the individual records are not yet catalogued but each file has a descriptor with date ranges, extents, condition and other key metadata. There will be a future job to catalogue all the item level records and to digitise the records. It took over 720 hours to catalogue the records to file level and though this has its limits they are still more accessible now then ever before.

The completed cataloguing increases the research potential for these vessels, their owners/builders and the events surrounding them.

Some vessels of interest: The Liberty (AKA the tower of silence), Endeavour II (First J-Class Yacht), Elektra (owned by Macroni), Oithona (purchased and run by the Marine Biological Association of the UK), Scotia (Arctic exploration) and Frank (first example of a Church mission yacht within the collection – fee for survey and travel also removed by LR). Some other vessels are noteworthy as being owned by Monarchs and Royalty across the globe, famous owners ( Renault and Jameson) or were used and saw action during the world wars.

Alongside records for yachts, we also discovered some surprises. Included in the files were over 100 files on vessels classed by the British Corporation, prize ships, ex-admiralty vessels and other non-yacht related material. Some of these records were believed lost or destroyed and can now be used to help facilitate better historical research. One of the most interesting of these finds was a file of records relating to the Empire Windrush.

REWRITING WOMEN

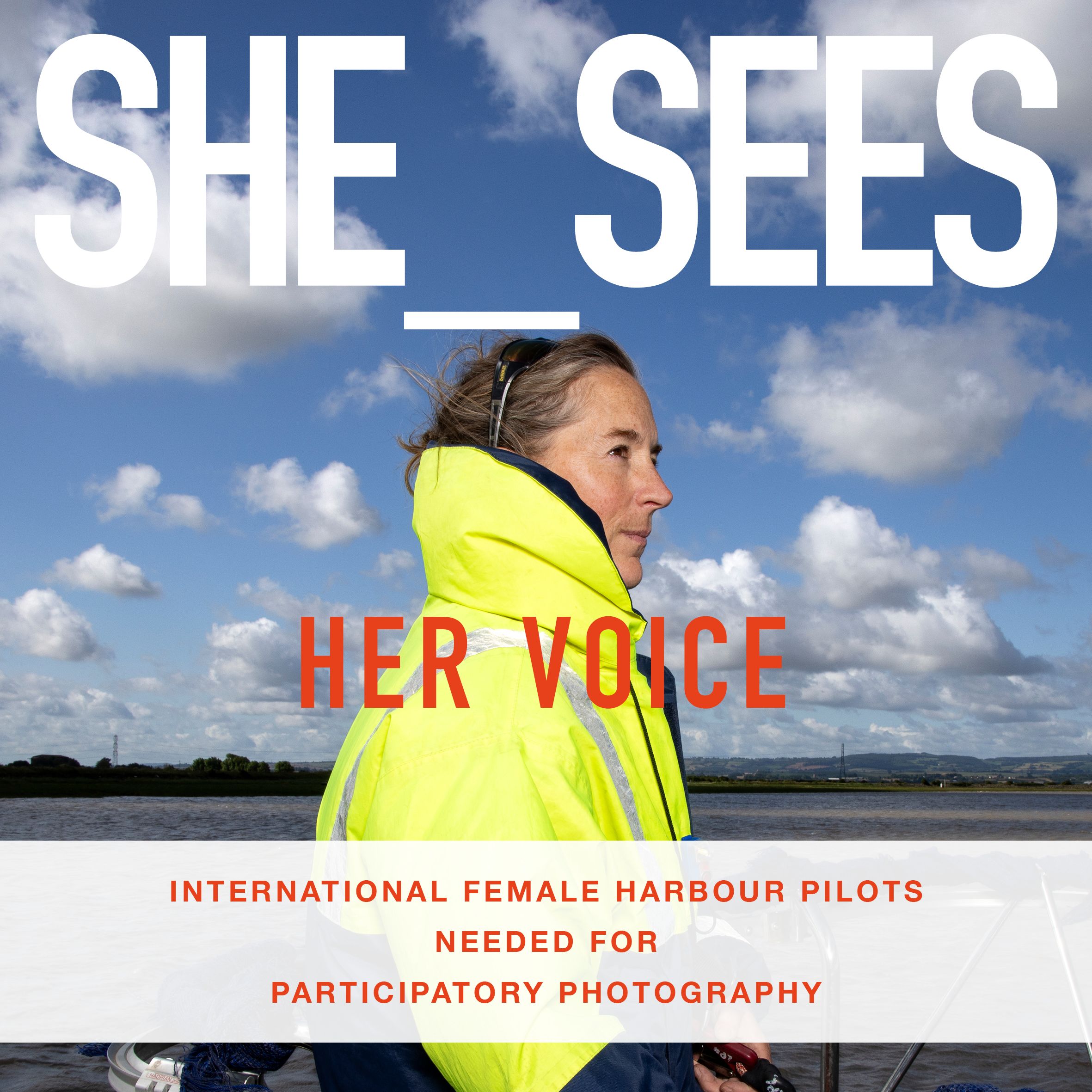

Earlier this year, Rewriting Women into Maritime History programme was signed off to take the initiative international.

1

H I S T O R I C A L STORIES

2

C O N T E M P O R A R Y PHOTOGRAPHY

3

T H O U G H T L E A D E R S H I P C A M P A I G N

A research hub. An online portal where stories of past and present maritime women globally to be signposted and made searchable all in one place, where people can submit and signpost interesting articles, initiatives and stories, so they are no longer silos of information floating on the web. Although the research hub will not be ready to launch for a few more years, we are still looking to gather, highlight and work with researchers and institutions on their historical research on women, primarily working within the regions we have identified to allow us to promote the historical narratives alongside the contemporary photography generated.

Rewriting Women will be continuing with our photography shoots but on a global scale. We aim to visit up to a maximum of three locations a year, starting with Greece in 2025. We are also launching SHE SEES, HER VOICE, a new participatory photography programme, where participants are empowered to tell their own stories through the lens of a camera. We are currently seeking eight International Female Harbour Pilots to participate in this online participatory photography programme.

How can we encourage active changes within the industry? Lloyd's Register Foundation are launching a Thought Leadership Campaign, that will interview leaders in the maritime space for their reflections on the current workforce and what needs to be done to make active change within the industry. In 2025, we will publish a report that addresses the top recommended action points for industry to take to advance diversity in maritime.

James Hunter is the Australian National Maritime Museum’s Curator of Naval Heritage and Archaeology. He has been involved in the field of maritime archaeology for nearly three decades and participated in the investigation of several internationally significant shipwreck sites. Since being appointed to the museum, he has participated in several of its premier maritime archaeology projects, including shipwreck surveys of Australia’s first submarine AE1 and Second World War light cruiser HMAS Perth (I), as well as the search for, and identification of, the wreck site of HMB Endeavour.

Using digitised Lloyd’s Register archives to analyse and identify historic shipwreck sites in Australia

Located in shallows a short distance off Stockton Beach near the Australian city of Newcastle are two elongated dark spots that appear intermittently, their respective sizes and forms continually altered by the movement of sand across the seabed. Positioned less than 0.3 miles (0.5 km) apart, one resembles a bullet with its business end pointed towards shore. The other lies parallel to the beach and – depending on its level of coverage – exhibits the unmistakable outline of a sailing ship, with two masts extending away from the hull into the surrounding sand. It is perhaps unsurprising these dark shapes so near to each other represent the remnants of two sailing vessels that came to grief on Stockton Beach. Somewhat unexpected is that they were both built in the 1860s at two shipyards located within 12.5 miles (20 km) of one another on Scotland’s River Clyde and their losses were separated by only a handful of years. These underwater apparitions that occasionally reveal themselves, only to again disappear beneath the shifting sands, are the wrecks of Berbice and Durisdeer.

Berbice at Stockton Beach shortly after being driven ashore. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

S C O T T I S H - B U I LT

Durisdeer was the first to slide down the slipway. Built at the shipyard of Alexander Stephen & Sons Ltd in the Glasgow neighbourhood of Kelvinhaugh, she was launched on 24 March 1864 as City of Lahore. The vessel’s hull was constructed entirely of iron plating and framing and measured 61.6 m in length. It had an extreme breadth of 9.7 m, a depth of hold of 6.5 m, and a registered carrying capacity of 988 tons. City of Lahore’s first owner was the Glasgow-based shipping firm George Smith & Sons, and her first voyage was from Glasgow to Bombay. The ship operated primarily between Scotland and ports in India until 1880, when ownership transferred to another Glasgow-based merchant, T.C. Guthrie. Renamed Durisdeer in 1882, she undertook its first voyage to the Antipodes the same year and was subsequently rerigged as a barque. For the remainder of its career, the vessel operated between Glasgow and ports in New Zealand, Australia, South America, South Africa and the West Coast of the United States.

The 717-ton ship Berbice was launched at the shipyard of Archibald McMillan & Son in Dumbarton on 25 April 1868. Its hull was of composite construction – meaning it comprised timber planking over iron framing – and had an overall length, breadth, and depth of 53 m, 9.6 m and 5.6 m. Berbice’s first owner was John Kerr of Greenock, Scotland and the vessel embarked for the West Indies on its inaugural voyage. Subsequent voyages would take the ship as far afield as India, the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia), South Africa, the Caribbean and South America. Following John Kerr’s death in 1872, ownership of Berbice transferred to his son Robert, who operated the ship under the banner of J. Kerr & Co. for the remainder of its existence.

V I C T I M S O F T H E O Y S T E R B A N K

The discovery of abundant deposits of coal in 1797 at what is now Newcastle led to the establishment of coal mines and the colony of New South Wales’s first major export economy. The need to transport coal from Newcastle to Sydney and points beyond, and bring convict labour and supplies to the mines, resulted in a significant increase in shipping entering and leaving the Coal River (now named Hunter River) from 1800 onwards. The entrance to the river was particularly treacherous for sailing vessels during the 19th century, as it was bordered to the north by a patchwork of shallow rocks and shifting sands known as the Oyster Bank. Immediately to the north of the Oyster Bank is the low, sandy coastline of Stockton Beach. This extends for 23 miles (37 km) to the entrance of Port Stephens and has been described as perhaps the most dangerous part of the Australian coast to approach in an easterly or south-easterly gale. The first vessel to fall foul of the Hunter River’s entrance was the sloop Norfolk, which – after being seized by convicts on the Hawkesbury River – was wrecked and abandoned in 1800 at Pirate’s Point on the far southern end of Stockton Beach. Its loss would be followed by that of at least one vessel per decade until 1977, when the MV Polar Star was wrecked at Stockton Beach. In the span of 177 years, nearly 300 vessels were lost within Newcastle Harbour and in the vicinity of its entrance, the majority falling victim to the Oyster Bank and adjacent Stockton Beach. Included among that grim tally were Durisdeer and Berbice.

Berbice’s wrecked hull soon became a popular attraction for visitors to Stockton Beach. Nobbys Head is visible in the background right of the photograph. Image: University of Newcastle Library Special Collections.

As part of our ongoing work to audit, appraise and catalogue our heritage material, the Heritage Centre has been working to identify and document our rare books so that they can be catalogued and made available to the public.

Special Collections are rare books and manuscripts that have more safety, conservation and access requirements than other library material because of their age and uniqueness. The cut-off date for something to be included as part of a Special Collection is typically around 1850, as after this period the majority of books are machine made on an industrial scale rather than using the processes that make each volume printed by hand unique.

Augustin Creuze

LRF/HA/2023/303 Title page of the oldest book in our collection

LRF/HA/2024/002 includes sketches of ships and a poem made by William Gibson

Lloyd’s Register’s Special Collections were first established in 1852, when Augustin Francis Bullock Creuze presented his collection of maritime and naval architecture publications to the General Committee. Creuze began working for Lloyd’s Register in 1844 as Principal Shipwright Surveyor in London. He was a prominent naval architect and judged improvements in naval architecture at the Great Exhibition in 1851. Creuze’s collection was accepted and rebound by the General Committee at a cost of 12 pounds and 15 shillings. Creuze died in November 1852, months after donating his library. After his death his widow offered the General Committee of Lloyd’s Register a collection of timber samples. The location of these samples and whether they were ever given to Lloyd’s Register remains unclear.

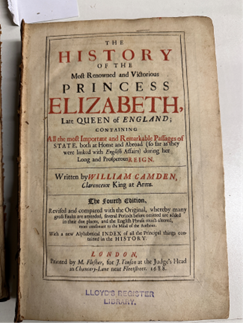

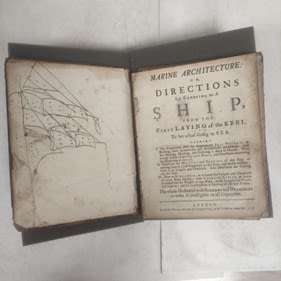

Since that first donation in 1852 LR’s Special Collections has continued to grow and we now have a collection of almost 400 titles. The oldest book in the collection is a biography of Queen Elizabeth I which was published in 1688, more than 70 years before the Society was founded. A favourite discovery is a volume full of annotations including doodles of ships and a poem made by a previous owner of the book called William Gibson.

Identifying all of our Special Collections involved a bit of a rescue mission when rare books were discovered hidden away in cupboards in our historic Old Library and had to be recovered and sent to our offsite processing area to be listed. Volumes in poorer condition have been stabilised with archival linen tape and wrapped in acid free tissue to prevent further damage. Volumes we found that were in especially poor condition have been sent for conservation so that they can be safely handled and exhibited in the future.

Every volume has now been identified and listed, meaning we have a full understanding of the extent and nature of our Special Collections for the first time. With this knowledge our Special Collections can now be catalogued ready to be housed in our purpose-built archive at 71 Fenchurch Street alongside our archive material. Once these volumes are catalogued, they can be safely made available to the public in our search room, through exhibition or online through digitisatio